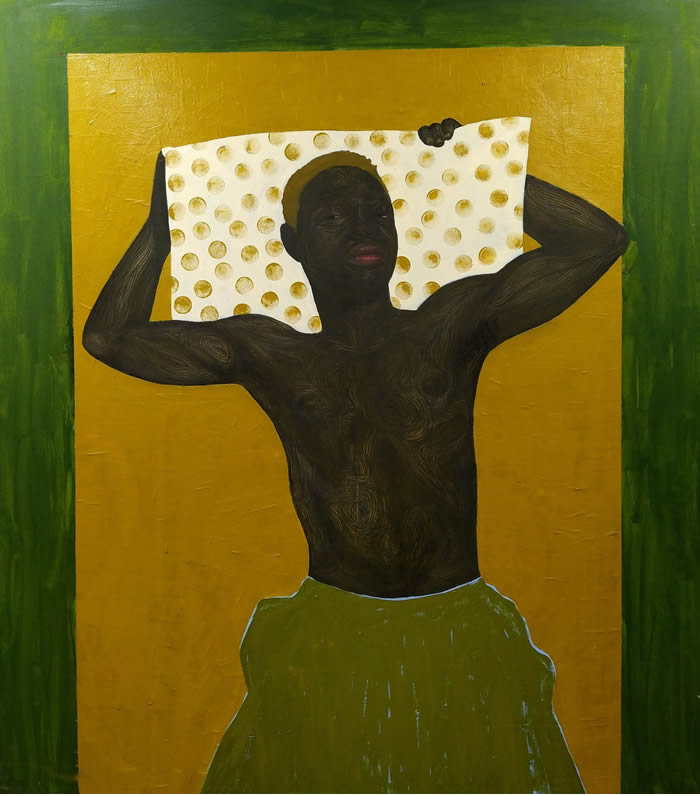

COLLINS OBIJIAKU

GINDIN MANGORO : UNDER THE MANGO TREE, 15 OCTOBER – 19 NOVEMBER 2020

“I can’t be a pessimist because I am alive. To be a pessimist means that you have agreed that human life is an academic matter. So, I am forced to be an optimist. I am forced to believe that we can survive, whatever we must survive.”

— James Baldwin

GINDIN MANGORO: UNDER THE MANGO TREE

Written by Azu Nwabogu

It is a curious thing to reflect on the nature of human existence and within this, its diversity. There is a lot of talk about diversity with regards to skin colour, gender, religion and so forth but the cruellest and most perverse form of diversity as human construct is that which we are most reluctant to speak of: the diversity of living conditions from one street to the next and one neighbouring country to another. We all live in our bubble and sound off in our own echo chambers but within all of these various states of existence there is a common desire to just be. To exist. To have the right to freedom of thought and space to ruminate and nurture our imagination. Where transcendence is a possibility and hope springs eternal.

Gindin Mangoro (Hausa) Under the Mango Tree, by portrait artist, Collins Obijiaku is a refreshing, questioning body of work and debut solo presentation whereby the artist proposes “to reach out to people and immortalise my friends”. As with all genuine attempts at portraiture, it goes much deeper.

In this first solo exhibition Obijiaku presents a selection of paintings with titles like “Passports”, and to his favourite “Gindin Mangoro” “Under the Mango Tree” this, a radical departure from his previous work based on social commentary. Obijiaku presents a new body of work as a celebration of his own lived experiences and struggles as well as those of his friends and acquaintances. He creates vivid and poignant portraits utilizing charcoal and texture to bring his subjects to life with dactylogram like lines, impressing notions of identity, space, patterns and typography. Close, focused observation of his styled portraits holds the viewers gaze in a dizzying embrace. This mesmerising effect induced by concurrent and collinear lines running with no obvious starting point or no known end is deliberate and for the artist these lines represent life’s unpredictable journey.

Obijiaku’s visual language plays with the now familiar theme of the profligacy of image production in relation to Black figuration and representation. But he cuts through the noise by crafting intricate musical lines which linger and resonate by means of deft counterpoint. The contours and lines of his work are like stand-alone rhythms and melodies which have been skilfully woven into polyphonies which are artistically satisfying not in spite of but because of their harmonic interdependencies.

He disrupts the natural order of image production in portraiture painting by texturizing his portraits in a such a manner as to suggest a sort of expressionism but not quite. The portraits do not speak to an expression of emotion but present each subject as an immortal destined for deification.

Obijiaku (b. 1995) was born in Kaduna, Northern Nigeria but has spent the last twenty years living in Suleja, a small town famous for its proximity to Abuja (the Nigerian Federal capital) and widely recognised as a town with a great pottery tradition. His creative ascent has been nothing short of meteoric.

Obijiaku’s creative journey started with sketches and comic illustrations blended into the margins of his class notes at secondary school. After his Secondary School education in 2016, he moved south to live with relatives in Enugu where he took up part time work in a shopping mall to earn his upkeep. After work hours he would stay behind for hours sketching on his notepad. Those early sketches and alone time allowed him to hone his craft and the vast expanses of the shopping mall sharpened his observational skills. He read people and perfected decoding their gaze. He studied the carefree, the wealthy, the working classes, those burdened with keeping the wheels of society turning and the diversity within, on a superficial level, a homogenous group of people. Obijiaku’s early pencil sketches were a form of release from the physical exertions of his job. A way to stimulate his mind, to find less clustered corners to freely imagine. He developed his particular style during that period with no formal art background or tutoring, simply continuing to nurture his obvious gifts as a draughtsman. He would paint and sketch friends and slowly started to gain commissions.

His return to Suleja after his sojourn in Enugu was with a fresh pair of eyes, ennobled sensibility from the sense that he has become a man, able to earn his own upkeep. This introspective awareness guided his personality and art. During this halcyon period, he witnessed his friend survive a near lynching in a case of mistaken identity, his timely intervention saved his friend’s life and triggered him to paint more purposefully and to chronicle the precarious existence of those on the margins of society. This was a turning point in his creative process. His paintings took on a darker, more sinister turn. Obijiaku stopped making commissions and invented a style of painting that focused on societal ills and injustices in the hope of catharsis. He observed the great inequality in daily living and begun a quotidian period of painting as a form of social commentary. Rather than offer him a release it drove him further into his shell. French cultural theorist Paul Virilio posited: “when you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash; and when you invent electricity, you invent electrocution…” Obijiaku had created a monster that was gaining critical attention but was also self-consuming.

Gindin Mangoro (2020), oil, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 180cm x 160cm